Fahrradhelme

Sheldon Brown und sein Umfeld waren Early Adapter von Helmen und haben mindestens einen Sturz hinter sich gebracht, bei dem die Landung auf dem Helm schwerwiegende Verletzungen verhindert hat.

Er riet zum Tragen eines Helms, glaubte aber nicht, dass eine gesetzliche Helmpflicht ein guter Weg sei, dies zu fördern.

Manche Helme bieten eine bessere Abdeckung und einen besseren Schutz als andere. Es ist empfehlenswert, eher die mit diesem bessern Schutz zu kaufen. Ein Helm sollte vorzugsweise eine helle Farbe haben, damit man tagsüber gut gesehen wird. Für gute Erkennbarkeit bei Nacht sind Reflektoren empfehlenswert. Am Fahrradhelm kann man wunderbar einen kleinen Rückspiegel, eine Kopflampe oder eine Miniaturvideokamera befestigen, auch wenn alle diese Erweiterungen ein mögliches kleines Risiko bei einem Sturz darstellen.

Noch ist kein Adler platziert.

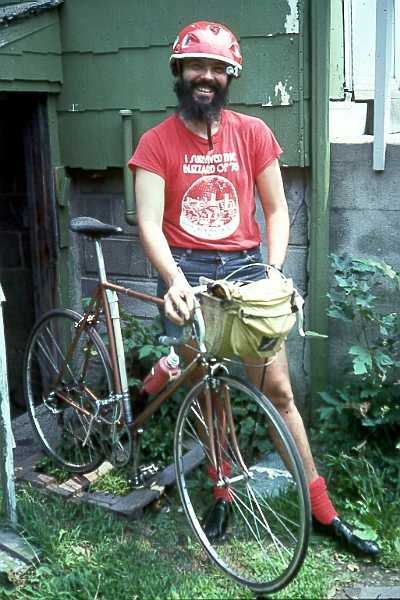

Auf dem T-Shirt steht (übersetzt) "Ich habe den Schneesturm 1978 überlebt".

Darunter ist eine Schneekugel mit einer Stadtansicht zu sehen. Das ganze ähnelt stark dem Helm...

Links in der Navigation dieser Seite ist das berühmte Foto von Sheldon Brown mit dem Adler zu sehen. Sheldons letzte bekannte Aussage zum Thema Helme, während er schon an Multiple Sklerose litt, war folgende:

Tatsächlich trage ich inzwischen keinen Helm mehr, weil ich nicht mehr in der Lage bin, Fahrrad zu fahren. Heutzutage fahre ich eine Liegedreirad, das so stabil ist und dessen Schwerpunkt so niedrig liegt, dass ich nicht glaube, dass ein Helm notwendig ist.

Sollte ich jedoch durch ein Wunder jemals wieder Fahrrad fahren können, trage ich sofort wieder einen Helm.

Der Helm schützt den Kopf gegen Einschläge von der Seite, von Hinten und insbesondere von oben. Zugegebenermaßen sind Einschläge von oben sehr selten - jedoch seitliche oder Schläge von Hinten sind bei Stürzen an der Tagesordnung.

Ich empfehle allen Fahrradfahrern, einen Helm zu tragen, glaube jedoch nicht, dass das durch eine gesetzliche Helmpflicht durchgesetzt werden muss.

Ich weiß nicht wie wahr die folgende Aussage ist, aber ich habe Berichte gesehen, die Nahe legen, dass bei der Helmpflichteinführung in Australien (oder war es nur einer der Staaten dort?), die Nutzung des Fahrrads so stark zurückging, dass der nachfolgende Anstieg an Todesfällen durch Herzkrankheiten höher war als die tödlichen Fahrradunfälle durch Kopfverletzungen.

Praktische und Rechtliche Aspekte

Bei den meisten Fahrradunfällen ist kein Motorfahrzeug beteiligt. Die meisten Stürze bei Fahrradunfällen - auch solche bei denen Motorfahrzeuige beteiligt sind - haben als Fallhöhe die Kopfhöhe. Diese Stürze sind in jedem Fall in der lage permanente Gehirnverletzungen oder -schäden zur Folge zu haben. Es existieren Studeien über Helme und Verletzungswahrscheinichketen die belegen, dass Helme diese Art Verletzungen verhindern oder redzieren sollten und es auch tatsächlich machen.

In Ländern wie den Niederlanden in denen das Terrain flach, typische Fahrradstrecken kurz und langsam sind, motorisierte Verkehrsteilnehmer sehr vorsichtig sind und Fahrräder Prioritäten genießen haben Fahrradfahrereine sehr geringe Verletzungs und Sterbequote. Dennoch würde das konsequente Tragen eines Helms bei holländischen Fahreradfahrern deren Sicherheit erhöhen. Fharradfahrer, die unter schwierigeren Bedingungen unterwegs sind, würden sogar noch mehr davon profitieren. Man kann feststellen, dass die gesundheitliche Vorteile des Fahrradfahrens diejenigen ausstechen, die durch das Nichttragen eines Helms entstehen. Aber warum soll man seine chancen nicht noch verbessern?

The popularity of helmets differs greatly from one country to another, and between types of cyclists and styles of cycling. Helmet use has been common among racers for many decades, and became nearly universal among avid cyclists in the USA and Canada within a few years after effective helmets became available. We understand that helmet use is also common in Sweden; it is required by law in some parts of Australia and to varying degrees (often, only for children) in some states in the USA.

Such laws requiring helmet use are very controversial, because people with a light commitment to bicycling may decide not to ride a bicycle if they are forced to wear a helmet.

Unless helmet use is already largely universal and strongly enforced -- not the case anywhere in the USA -- laws are less effective than helmet promotions in convincing people to wear a helmet. Strong support for these laws, however, comes from outside the bicycling community, and if a helmet law is going to pass, it needs very close attention to avoid devastating unintentional consequences. A bicyclist's not wearing a helmet should not be admissible in a court of law as evidence of fault in a crash. This liability exclusion is usual in safety-equipment laws, to avoid placing the legal responsibility for a crash on someone who was operating according to the rules of the road. Well-meaning safety advocates often are unaware of this issue.

Aside from compulsory helmet laws, the primary helmet issue to an individual is the risk that he or she is willing to take (and to impose on family, friends and society at large) -- versus the cost and inconvenience of the helmet.

An individual making a free-will decision to purchase and wear a helmet probably has already decided to ride a bicycle. An individual forced by law to wear a helmet may not have made that decision, and some studies show a reduction in bicycle use if helmet laws are enforced. Also, some studies that look at a population at large show no reduction in fatality rates with helmet laws. This situation has been attributed to a low actual percentage of helmet use and by some to "risk homeostasis" -- that cyclists who wear helmets might compensate by taking more risks -- which, on the other hand, can mean riding more and taking trips that would otherwise be avoided.

Die Geschichte des Helms

Bicycle helmets have evolved over the years, but the bicycle helmet as we now understand it first appeared in the mid-1970s.

Bicycle racers commonly used the so-called "leather hairnet" until better designs with optimized impact protection superseded it. A few cyclists, notably Dr. Eugene Gaston, medical columnist for Bicycling magazine, had taken to wearing hockey or mountaineering helmets around 1970. Club riders and racers saw the need for head protection, but there was not yet a helmet optimized for best protection compatible with light weight, unobstructed vision and ventilation.

Around 1973, a Seattle, Washington, USA company, Mountain Safety Research, introduced a modified mountaineering helmet which used cloth webbing attached by eight deformable side clips to provide impact absorption. MSR later added EPS (expanded polystyrene) foam inserts between the webbing straps. The next year, Bell introduced the Bell Biker, the first helmet designed from scratch specifically for bicycling. It used EPS as its impact-absorbing material, and had tapered ventilating inlets, as do most other bicycle helmets made since.

Standards and test methods for bicycle helmets have been set (in the USA) by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), the Snell Memorial Foundation, the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and currently, the United States consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Helmtypisierung

Modern bicycle helmets have been of three main types:

- Hardshell: The MSR and Bell helmets, and other early ones, were of this type. They had a hard plastic shell, to resist penetration by pointed rocks, curbs, etc. Most skate-style helmets are still made this way.

- No-shell: for a short while, in the late 1980s, helmets were produced with the expanded polystyrene shell covered only by thin cloth. The first such helmet was developed by Jim Gentes, who founded Giro. This helmet passed the helmet-testing standards of the time and weighed less than other helmets, but questions arose as to whether the polystyrene might snag on rough pavement, causing brain and neck injury due to head rotation. Also, such helmets would often break apart on impact.

- Thin-shell: The plastic shell is too thin to provide protection against object penetration, but it does provide a smooth surface to avoid snagging on rough pavement, and helps to hold the helmet together on impact. In high-end helmets with big vents, reinforcing of plastic, nylon or more exotic materials is molded inside the expanded polystyrene. Most helmets made and sold since 1990 are thin-shell helmets.

Bicycle helmets over the years Hairnet MSR, 1973 Bell Biker, 1974 Hairnet helmet (Helmet wearer unknown) MSR helmet, 1974 (Helmet wearer is Milt Raymond, Boston-area utility cyclist and inventor.) Bell Biker helmet, 1974 (Helmet wearer is Jacek Rudowski, avid Boston-area recreational cyclist.)

No-shell, 1990 Thin-shell, 2004

No-shell helmet (The helmet wearer is John Torosian, then President of the League of American Wheelmen.) Thin-shell helmet (The helmet wearer is Tom Revay, an avid Boston-area commuter and recreational cyclist.)

Helmdiskussion

There has been heated controversy ("helmet wars") among cyclists and cycling advocates about helmet laws and helmet use. Helmet skeptics are primarily libertarians opposing helmet laws and riders who see helmet advocacy as unthinking protectionism. Although small in numbers, they are adamant, and fill blogs and bulletin boards with anti-helmet messages, giving rise to the term "helmet wars".

Bicycling advocates who dismiss helmet use generally assume that the greater good is achieved by convincing more people to ride bicycles, even at the expense of avoidable injuries. Helmet advocates, on the other hand, have included not only many safety-conscious cyclists but also generalist safety advocates -- in particular in the USA, Safe Kids USA. Both sides have more in common than they might think: both like to make decisions for other people. Both often fail to consider unintended consequences. Helmet opponents consistently deny the robust scientific data supporting helmet use. Non-cyclist helmet advocates have had to learn that there is more to safe bicycling than helmets; that promotional campaigns and helmet giveaways to low-income people are more effective than laws; and that fairness requires a helmet law to include a liability exclusion.

It's a classic case of imposing of one view or another of the interest of society, versus self-interest based on an individual's best judgment. The "dangerization" of bicycling has a bad taste for us, but so does dismissal of the real benefits of helmet use.

It has correctly been asserted by advocates on both sides that avoiding a crash is preferable to crashing in a helmet. But beyond this, safer roads, careful and skillful cycling and use of other safety equipment, particularly lights at night, reduce injury risk to the entire body more than wearing a helmet on the head. Physical exercise from bicycling increases life expectancy more than risk decreases it, even without a helmet -- though this last argument fails to take quality of life into account. Exercise increases life expectancy by a few years for large number of people, while helmet use can increase it by decades for those who crash, and also prevent long-term disability. There is also no reason to think that bicycling is the only form of exercise that a person avoiding helmets would use.

Web sites for more information on helmets and the helmet wars issues:

- Pro: Bicycle Helmet Safety Institute (US)

- Con: Bicycle Helmet Research Foundation (UK)

Quelle

Dieser Artikel basiert auf dem Artikel Bicycle Helmets von der Website Sheldon Browns. Originalautor des Artikels ist Sheldon Brown.